What are Invasive Plants & How it Affects Your Yard

By Axis Fuksman-Kumpa • October 6, 2022

If you’re a home gardener, you’re probably well aware of how problematic invasive insect species can be—we’ve all had to pull more than a few Japanese beetles off our plants. But what about invasive plants? It turns out they can be just as damaging to the ecosystem without most people ever noticing.

What Are Invasive Plants?

Invasive species are living organisms that can cause ecological harm when they’re introduced to a new, non-native environment. This can include anything from mammals (like rabbits in Australia) to reptiles (Burmese pythons in Florida) to sea creatures (zebra mussels across the U.S.) to insects (spotted lanternflies in Pennsylvania) to plants.

Invasive plant species are typically brought to a new area with good intentions to serve as an ornamental plant or to fill a niche in the ecosystem. Kudzu, for example, was brought to the United States from Asia in 1876 as nothing more than a beautiful vine for people’s gardens.

From the 1930s through the 1950s, the Soil Conservation Service actually encouraged people in the South to plant kudzu to help prevent soil erosion. However, the vine was far more tenacious than anyone expected and it has now spread over large swaths of the Southern landscape and migrated across North America.

Many invasive species are a perfectly healthy part of their natural environment. Japanese beetles and kudzu both have a perfectly healthy niche in Japan’s ecosystem where they have natural predators. It’s introducing a plant to a new environment that poses a risk. Even with the most careful planning, these foreign additions to the landscape can have unforeseen consequences.

It is also important to note that not every non-native plant is an invasive plant. Many common garden plants in the United States like Asian hydrangeas and hostas aren’t originally from here, but won’t overtake the native plants in your landscape.

Japanese Beetle

Japanese Beetle Kudzu in Atlanta

Kudzu in AtlantaHow Can Invasive Plants Harm the Environment?

Reduced Biodiversity

Most invasive plants are dangerous due to their ability to grow prolifically and out-compete native plants. Healthy, natural ecosystems rely on having a wide variety of plants to sustain the whole food chain. Replacing native species with invasive ones forces out animals that rely on them to live and can create dangerous monocultures of the invasive species.

Decline in Wildlife Habitat

Every animal in the food chain depends on native plants to live and thrive. Native plants provide both food and shelter for numerous species, and their significance is often much deeper than we realize.

For instance, adult songbirds can chow down on birdseed, but baby birds depend on soft-bodied caterpillars as food in the spring. According to native plant expert Doug Tallamy, “Ninety percent of the insects that eat plants can develop and reproduce only on the plants with which they share an evolutionary history.” That means that if the native host plants for caterpillars are forced out by invasive species, not only would the caterpillars die—so would a whole generation of birds.

Increased Fire Risk

One of the many problems with a monoculture is how vulnerable they are to threats like disease and fire. When a wildfire moves through an area with a diverse ecosystem, it’s slowed down as it has to leap between plants of different heights and flammability, giving animals time to flee.

Monocultures of invasive species change this dynamic as highly flammable species like cheatgrass let fires rage uncontrolled and vining species like English ivy can actually help fire to climb trees and burn the canopies, which would typically be left unscathed. These types of fires are much more dangerous to both wildlife and people, and leave a blank canvas devoid of life. That means invasive plants can return and once again choke out native plant growth, replacing full forests with invasives.

Worse Water and Soil Health

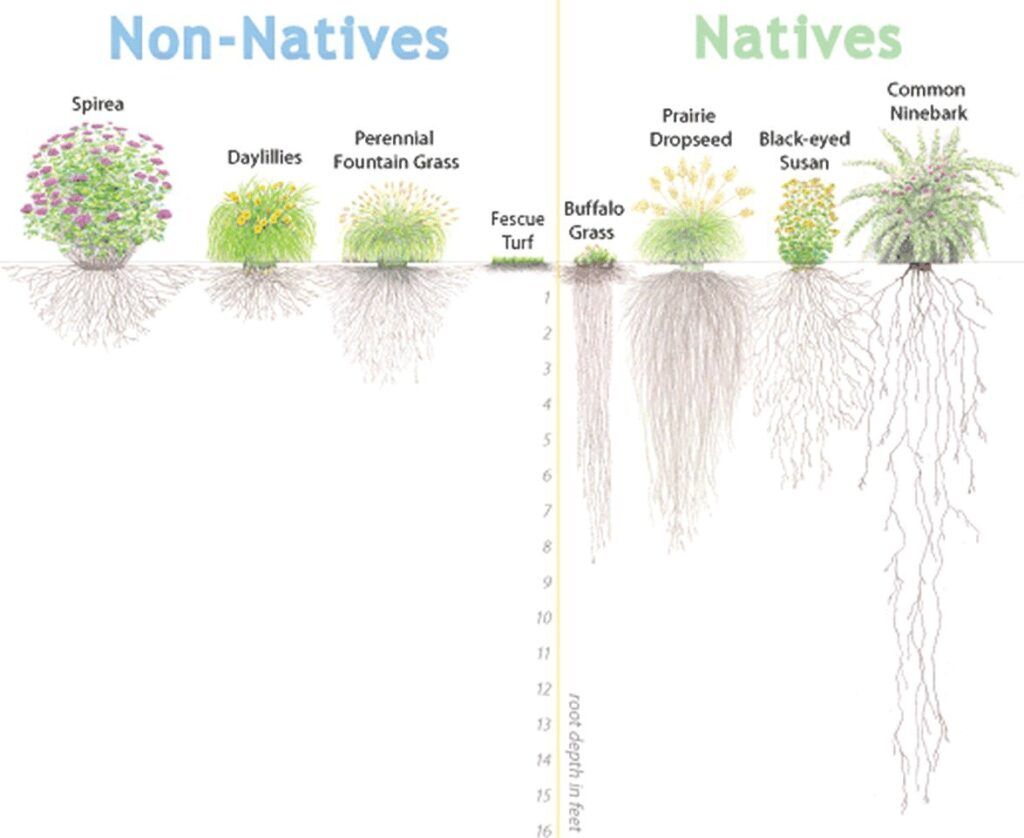

Many native plants are well-known for having deep and wide-spread root systems. These root networks help to stabilize the soil and prevent rapid erosion. However, invasive species kill off these well-established plants and their root systems to replace them with their own shallow roots (which are common in young and quick-spreading plants). When the soil isn’t stabilized, it’s left vulnerable to erosion from wind and water, leaving the area vulnerable to landslides and collapsed riverbanks which muddy the waters.

What Does Invasive Plant Species Damage Look Like?

It can be difficult to imagine this damage in the real world, but people around the globe are surrounded by the effects of invasive plant species. In South Africa, invasive American Chromolaena odorata is shading normally sunny Nile crocodile nests, cooling them down and resulting in the birth of many more female crocodiles than normal and entirely changing the balance of the crocodile population.

Invasive plants have a dangerous effect on pollinators as well, damaging their natural food sources and possibly the pollinators themselves. Monarch butterfly populations have declined by 85% in the last two decades due in part to the diminishing availability of milkweed, their only host plant, which is being challenged by invasive species like black swallowwort across the Americas.

The rare West Virginia white butterfly was already declining in its native habitat across the eastern U.S. due to deforestation when invasive garlic mustard reached its territory. The butterflies showed an immediate preference for this new plant over their traditional food source, toothworts (another member of the mustard family). Unfortunately, the garlic mustard plant contains chemicals that are harmful to the butterfly’s eggs, meaning that West Virginia white eggs laid on the plant never hatch at all—further damaging the population of this vulnerable pollinator.

Human activities aren’t untouched by the effects of invasive plants, either. While we will undoubtedly feel the ripple effects of damaged ecosystems and pollinator populations, the damage is felt directly in farming communities around the world.

The Oregon Invasive Species Council has estimated that invasive plant species cost the U.S. economy $120 billion dollars every single year in lost crops, plant control, damaged property, reduced livestock production, and reduced exports. That cost hits farmers’ wallets and is also felt by consumers as we pay higher costs for food produced under threat from invasive species.

How Can We Help?

The most important things citizens can do to help prevent the spread of invasive plants and protect our ecosystems are to:

- Learn to recognize invasive plant species

- Plant and protect native plants in our environment

You can find your own area’s invasive plant species by checking the state-by-state lists on the USDA’s invasive species database. Once you learn to recognize them, you can remove them from your own backyard and feel free to do a little weeding on your next hike. If you notice invasive species spreading in your area, you can report it and help scientists track the movement of invasives.

When it comes to your own backyard, that’s where you can go wild with native plants! Doing so will help to support the biodiversity of your environment and create habitats and food sources for wildlife, and it doesn’t have to be difficult with simple Plant Finder tools to help you find the right native plants for your area. And before you worry about having to say goodbye to your tulips, this doesn’t have to be all or nothing.

Remember Doug Tallamy, the authority on native plants? After he filled his own backyard (which used to be a hay field) with native plants, he recorded over 100 new insect species in the area in just a single year—a massive victory for biodiversity. He wants to bring that same success to others with the Homegrown National Park project.

His goal is to replace just 50% of America’s vast, empty lawns into an ecologically productive space with native plants. That doesn’t take a lot of money or expert installation, but would re-wild over 20 million acres of land—that’s the equivalent of almost ten Yellowstone National Parks.

“Every little bit helps,” Tallamy says. “The minimal thing is, you plant a tree and it’s the right tree. Look at what’s happened at my house.”

The National Wildlife Federation™ took these ecological standards even farther with their Certified Wildlife Habitat® program. You can certify your backyard to show that it includes native plants and a range of other features to support local wildlife.

You don’t have to do this alone, either. Tilly has partnered with the NWF to train our designers in creating Certified Wildlife Habitat® designs. That means we can help give you the eco-friendly yard of your dreams!

Read more about: Gardening Tips